A further weakness is a reliance on long expositional speeches that it’s hard to imagine anyone actually saying. And, since you can’t possibly explain everything, the reader is sometimes left wondering why the narrator hasn’t also told you what’s happening in the cold war, or China, or how he has ended up with a glass of Moldovan white wine in 1982, when the country, then Moldavia, was part of the USSR. To my taste, this is a flat-footed way of doing sci-fi. Innocence never has much of a chance in McEwan’s novels.

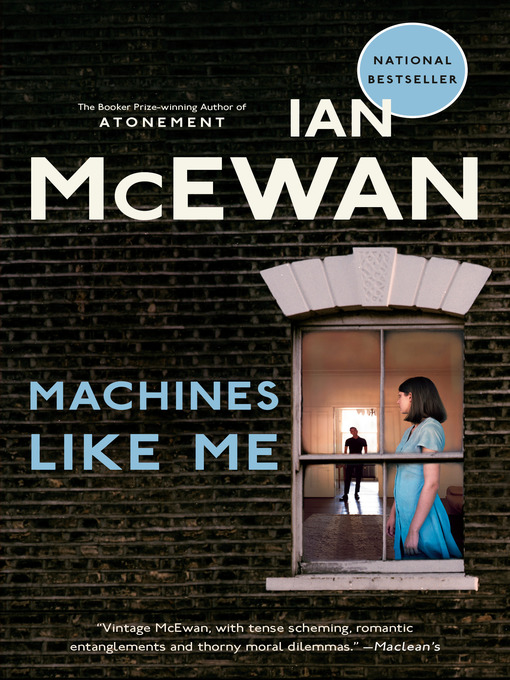

McEwan has always written stunningly about children. As for McEwan’s characters, Charlie can be an irritant, but Miranda is compelling. And, to repeat, all he’s doing is taking him out of a closet. There’s a passage in which Charlie takes Adam’s powered-down body from a closet that’s so viscerally written it scrapes your nerves like a horror movie. Machines Like Me moves briskly even when it gets hard to pull a comb through its plot. In fact, Machines is about what most literary novels are about: the godawful messiness of being human. Having said all this, Machines Like Me is no more out-and-out science fiction than Kazuo Ishiguro’s elegiac novel about clones, Never Let Me Go. Still, there’s something moving about a novelist assiduously reconfiguring history just so one good man can live. In recent books, McEwan has sometimes been too showy with his research, and Machines is one of those sometimes: His explication of the world’s revised timeline is disruptive and atonal. Ultimately, it asks a surprisingly mournful question: If we built a machine that could look into our hearts, could we really expect it to like what it sees?.

Machines is a sharp, unsettling read, which-despite its arteries being clogged with research and back story-has a lot on its mind about love, family, jealousy and deceit. Yet he’s such a masterly writer of prose and provocative thinker of thoughts that even his lesser novels leave marks. It is not the first, or even the 10th, place to start reading McEwan if you’ve never encountered him before.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)